I have been thinking hard about values and ethos recently. It’s probably to do with being on NPQH where every other slide on every PowerPoint is about your values and vision, but my thoughts were also prompted by Joe Kirby’s recent blog series on rewards which begins with the Lewis Carroll quotation:

“Everybody has won, and all must have prizes”

I remember David Cameron using this same quotation post-Olympics as he laid out his vision for the future of a Conservative-led Britain in the pages of the Daily Mail:

“In schools, there will be no more excuses for failure; no more soft exams and soft discipline. We saw that change in the exam results this year. When the grades went down a predictable cry went up: that we were hurting the prospects of these children.

To that we must be very clear: what hurts them is dumbing down their education so that their potential is never reached and no one wants to employ them. ‘All must have prizes’ is not just patronising, it is cruel – and with us it is over.”

I find this difficult, because I’m caught on the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, I’m a fan of competition. I know that it can spur people on to achieve bigger and better things. I’ve been listening with interest to the documentaries commemorating the first four-minute mile, run by Roger Bannister on 5th May 1954. Most commentators, and Bannister himself, agree that competition from Australian John Landy pushed him on to achieve that feat. Kennedy’s drive a decade later to put a man on the moon was driven more by competition with the Soviet Union than scientific advance.

I’m also a fan of competitive sport, both as a spectacle and as an integral part of schooling within and beyond the curriculum. Despite all of this, I can’t help feeling uneasy at the notion of awarding prizes to the single best performer in a discipline.

I’m certain this unease has its roots in my own experience; schooling is formative for all of us. But unlike Michael Gove, I am not driven to emulate my own schooling for the students in my care. My school (all boys, independent – read about it here) was competitive in every respect from the entrance exam to the end-of-year prize-giving; all very well if you were the single person that won. Which, after the first year, I was – I won the subject prizes for English and Biology and went up to shake the Headmaster’s hand the day after the great storm of 1987. From that point forward, I measured myself against the success of others, constantly looking over my shoulder at the competition – the epitome of a fixed mindset. It’s no wonder that Carol Dweck’s story about being sat around the room in IQ order in sixth grade strikes such a chord with me! In the Sixth Form, when the school prizes were awarded, I came second in English. And I was gutted.

Let’s put this in context. I had a place to read English at Oxford; I got an A at A-Level and a 1 in S-Level English – and I was disappointed. Because there was someone better than me. It turns out the teachers were probably right, since the prize was awarded to my contemporary and all-round lovely bloke Andrew Miller, who went on to write the Man Booker nominated Snowdrops (heartily recommended by the way – a fantastic novel). I should have been proud of my achievements, but I wasn’t, and this was entirely due to the competitive ethos of my school where only one person could feel truly proud of what they had achieved – the winner.

I have no doubt that Cameron, Gove et al would nod at this and say “quite right.” In a true meritocracy, I wasn’t good enough. Perhaps they might even say that without the competitive ethos I would not have achieved as highly as I did. But I can’t accept that. In a growth mindset we should be measuring performance against our own yardstick, aiming to better our own personal best irrespective of the performance of others. This is the message I teach in my classes, the ethos I want for my school, and the frame of reference I set myself.

The same idea permeates my attitude to prefects and student hierarchy. My school had three levels – house prefects (bronze badge), sub-prefects (silver badge), and prefects (gold badge). As I’ve said, it was an independent boys’ school, so what do you expect? I was a sub-prefect but was never nominated as a prefect – I still don’t know why. The criteria weren’t published. I was certainly never in trouble, I was academically successful, I had 100% attendance throughout my school career. I wasn’t sporty; was that it? Maybe I wasn’t high-profile enough. Maybe there was a quota which had already been filled. My point is this – I had done my best throughout my schooling, and I was left disenchanted. A good student, passed over, left resentful and irritated, feeling second-best when there was no need! That’s why I strive in my classes to recognise the achievements of every single student, not to pass over any of them, and to celebrate each of them.

I wish I’d gone to the school I teach at now. There are no prefects, no Head Boy or Head Girl with their own offices and privileges putting them a cut above. The thriving school council, branded Change & Create, is comprised of self-generated student-led teams engaged in projects such as fundraising, Amnesty International, caring for the chickens, gardening, regenerating the pond and memorial garden, caring for wildlife, raising awareness of mental health issues… If a student wants to be part of it, they step up and join or form a project team. This way the community of the school pulls together towards common aims without the interference of hierarchy or external judgement. It is growth mindset in action.

And yet…we still have prizes. Each year the highest performing student in each subject discipline receives an award. Every school I’ve ever worked in has had them. And, for the winners, they’re great. The public recognition of achievement is powerful and important. We temper it slightly with awards for “most progress” and “best effort” alongside the achievement awards, which I think helps. And thankfully, we don’t have the situation which prevailed in a previous school where students were only permitted to receive one prize, which led to the bizarre situation of having my Media Studies nominees returned because they’d already been nominated in Art or Chemistry or something, so the second best media student would get the prize…and the senior leader in charge would not be budged. Insane!

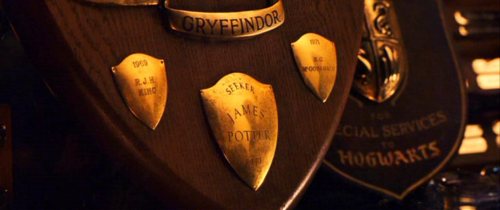

The prizes themselves bring something else, however – a story. They’re named after an ex-teacher, ex-student, or member of the school community who wanted to put their name to an award. Some of them stretch back decades, some are more recent. Every year, as the story behind the award is read out, I get a lump in my throat: “this award is in memory of…a servant of the school for thirty years…” The names of the recipients are recorded, and it connects us to a shared community history that helps make the school more than a set of buildings and a seat of learning. I love this part of the prize-giving ceremony. I just wish there was a prize to recognise and reward the efforts of all our learners for the victories, achievements and triumphs they have celebrated on their journey with us.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Pingback: Points about prizes | Articles and blogs for AC...

Pingback: ORRsome blog posts from the week that was. Week 21 | high heels and high notes

Reblogged this on Excellence & Growth Schools Network.

My step-daughter’s school has prizes for the best in each subject in each year. It has been a massive irritation for us. In Year 7 she came top of her class in science tests consistently (she believes), and of course she should as she could balance chemical equations and work out molecular formulae using electronic structures at that age etc – her irritating science teacher parents had helpfully taught her. Yet she wasn’t even nominated in the top three. Her friend, who my step-daughter claims to have consistently beaten in tests did get nominated though (different teacher). In Year 8 she won the humanities prize. So where are her interests now? Giving her a badge for geography has helped to boost her interest in the subject and not nominating her for science has undermined her confidence in her science teacher. In Year 9 she won the humanities prize again, but she felt her friends deserved it more than her.

We had prize giving at the school I attended, but it was only for GCSE and A-level results. It was based on UMS scores and therefore not a great concern to myself or my peers.

Not a fan of prize givings based on ‘teachers liking you’ having seen it from the point of view of the parent!

I completely agree. Where there are clear criteria – as in the UMS example you gave – I think there is less of a problem. It seems to me that there is more potential to do harm than good, as prizes are really only good for those that win them (and sometimes not even them!). Thanks so much for the comment, which is a really helpful perspective.

Pingback: 2014 in review: my second year of edublogging | Teaching: Leading Learning